|

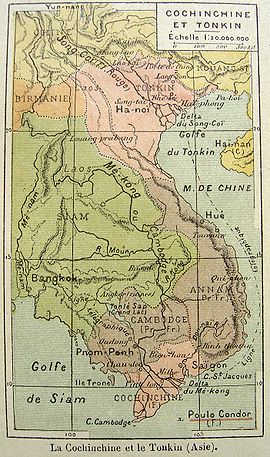

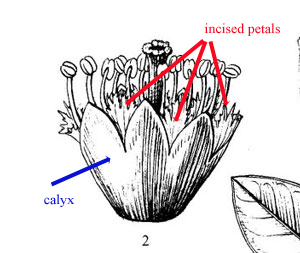

In 1805 Candolle's generic name Diatoma was new among algae, and the word had not yet surfaced attached to minerals, but it was not new among flowering plants. João de Loureiro (1710-1791), a Portuguese Jesuit missionary who lived in southeast Asia for forty years (1738-1780), assembled substantial collections of and notes on the region's plants. From about 1780 he corresponded with and sent specimens to Sir Joseph Banks, then a prime-mover of British botany, who evaluated his descriptions of new plants, many of which he judged as previously described. Nevertheless, Banks supported and advocated the publication of his work, Flora of Cochinchina [Flora cochinchinensis], which occurred in Lisbon in 1790, the year before Loureiro's death. Cochinchina was the southern region of what is now Vietnam dominated by the Mekong River where it interfaces in a broad delta with the South China Sea (Figure 28). In his examination of its flora Loureiro discovered a plant which he placed in a new genus of freshwater mangroves, and which he named Diatoma. He differentiated it partly from the then-known marine mangroves (genus Rhizophora) by its flowers in which the corolla had petals which were incised or split: "Cor[olla]. petals 6-7, sub-rotunda, incisa, ...", and indicated the characters of the genus as: "Char. Gener. Cal[yx] baccatus, 8-fidus. Cor[olla] 6-7-petals incisa, ..." [my bold]. He was clear about the name:

Diatoma

meant "incised, notched", not a bad fit for Candolle's descriptor

of the confervoid filament to which he gave the same name 15 years later

in the Flore. Evidently Candolle was either unaware of Loureiro's work or at least did not recall his use of the name Diatoma. We might expect he had seen Flora cochinchinensis given its being the first major flora of southeastern Asia and including many new and medically interesting plants, a subject in which Candolle took great interest. Also a copy of the Flora was in the hands of Antoine-Laurent de Jussieu, a fatherly colleague of his at the Muséum from 1798-1806, and who had edited the work and found, in contrast to Banks, most new species actually new and not previously described. But as one even just skims the first decade of Candolle's botanical life, it is readily understandable that he might have missed the name. Commencing in 1794 with botanical studies with Jean-Pierre Vaucher in Geneva, he then worked on vegetable physiology with Jean Senebier, who would discover the exchange of carbon dioxide and oxygen in plants, and then with H-B de Saussure, emphazising math and physics, and attended lectures at the Muséum in Paris. He began publishing in 1798 and by 1802 had written nearly 20 papers, some brief: initially on a slime mould (myxomyxcete) from the Juras, on a kind of gum from beech, on lichen nutrition, on marine plants, on some Siliculeuse genera (1798), on the effects of light on plants (1800) -- and some not-so-brief: the early issues of a History of Succulent Plants and Grasses (1799-1803), illustrated by the Belgian watercolorist Pierre-Joseph Redoubté, the first two volumes of Les Liliacées, again with Redoubté and a treatise on locoweed (Astragalus). By the end of 1802 he had committed himself to the revision of Lamarck's Flore, a revision that involved a complete restructuring, corrections, and addition of 3600 new descriptions. While he was focused on the Flore revision, he also completed his medical degree, published his dissertation of medicinal plants, and other papers on irises and for encyclopedias, and lectured for Cuvier at the Muséum. Not suprisingly he therefore admits, or indeed, laments, that during this period up to 1805 he had neglected "the foreign families" of plants.

Figure 31 (right). From Lamarck, J. B., & J. L. M Poiret. 1811. Botanique. In Encyclopédie méthodique: ou par ordre de matière;: par une société des gens de lettres, de savans et d'artistes .... Supplement, Tome 2, p. 469. |

|

In 1824 Candolle started a preliminary

account of all plant species on the globe. By 1828 as a part of this

work he came to examine a group of tropical and subtropical trees, shrubs

and vines in the family Combretaceae, for which he was confronted with

picking a genus to represent the family nomenclaturally. At this time

the Combretaceae included Loureiro's genus Diatoma. And so, in

a very matter-of-fact footnote in a paper in the Mémoires

de la Société de Physique et d'Histoire naturelle de Genève

(1828) he records his thoughts about uncovering the prior Diatoma:

Candolle finally, after 23 years, is explicit about the meaning and derivation of diatome. It refers to the transverse apparent cuts in the filament - "the plant ... is cut crosswise" - as we had thought; it agreeably conforms with Loureiro's "incised or notched." And emphatically, Candolle indicates diatome does not describe the plant as consisting of two fragments or bits! -- a response to Bory de Saint Vincent's mis-characterization of the meaning of the name. Bory had written in 1824:

Bory addresses not any division within a segment (article, cell) but rather between them; his counts refer to the number of segments (cells) one might find in a filament. Candolle basically rejects the idea the name refers to "two" of anything. The word atom itself is a combination of a- and -tom, hence, meaning without division, uncuttable. Two atoms, di-a-tom -- two indivisible bits -- has found application in chemistry, such as in the diatomic molecules of N2 and O2. But, as applied to organisms the word diatome conjoined the Greek roots of dia- and -tome into a two-rooted word, not a three-rooted one. Dia- in Greek means "across" or "through", not "two." Candolle's footnote leaves no doubt. |

| <-- 7 - Minerals, cleavage & Haüy |

Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License

8

- Loureiro's Diatoma

8

- Loureiro's Diatoma

Figure

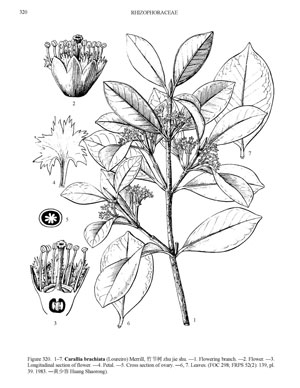

30 (left). Carallia brachiata (Loureiro) Merrill. (Syn. Diatoma

brachiata Loureiro, Fl. Cochinch. 1: 296.) Flora of China.

The incised petals are shown in the drawing on the right (red arrows),

just inside the surrounding calyx. http://www.efloras.org/object_page.aspx?object

Figure

30 (left). Carallia brachiata (Loureiro) Merrill. (Syn. Diatoma

brachiata Loureiro, Fl. Cochinch. 1: 296.) Flora of China.

The incised petals are shown in the drawing on the right (red arrows),

just inside the surrounding calyx. http://www.efloras.org/object_page.aspx?object One

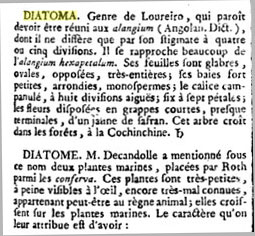

can readily find French encyclopedias of the period with Diatoma/Diatome

side-by-side (Figure 31). But for the next two decades, having left

Paris in 1806, spending 8 years at Montpellier before settling in Geneva,

Candolle's literature is silent about the name conflict.

One

can readily find French encyclopedias of the period with Diatoma/Diatome

side-by-side (Figure 31). But for the next two decades, having left

Paris in 1806, spending 8 years at Montpellier before settling in Geneva,

Candolle's literature is silent about the name conflict.

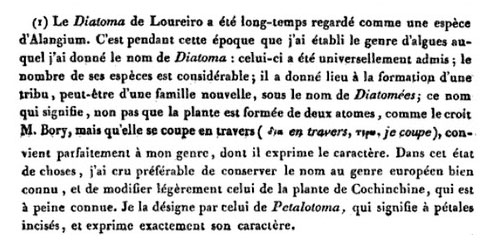

Figure

32 (left). Footnote

from Candolle, A. P. 1828. Sur le Combretaceae.

Mémoires

de la Société de Physique et d'Histoire naturelle de Genève.

Figure

32 (left). Footnote

from Candolle, A. P. 1828. Sur le Combretaceae.

Mémoires

de la Société de Physique et d'Histoire naturelle de Genève.