|

7 - Minerals, cleavage and Haüy

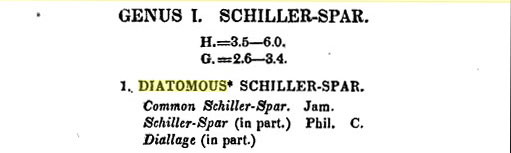

Figure 18 (above). From J. D. Dana's

System of Mineralogy (1837).

|

|

|

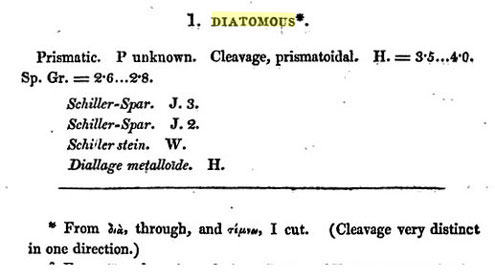

And five years earlier, in 1832, Dartmouth College's

Ebeneezer Emmons' entry in his Manual for "Diatomous* Schiller-spar"

(Figure 20) had borne a footnote also explaining the origin of diatomous:

Figure 20 (right). From E. Emmons' Manual of Mineralogy and Geology (1832), p. 100. |

|

|

To both these American geologists diatomous meant "to cut through, to cleave". The similarity to the meaning of diatomes inferred from Candolle in the Flore aroused my curiosity as to whether the term arose independently. Not that Candolle got it from them, but where did the Americans get it? And could Candolle have gotten it from there also? Was there an earlier history of this word in mineralogy that Candolle might have tapped? My recalling a lecture and works by Peter Stevens on the historical development of botanical systematics suggested there might well be -- with the connection being the generally recognized "father of crystallography", the French Abbé René-Just Haüy (Figure 21). |

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 22 (left.) René Just

Haüy (1743 - 1822). Essay on a theory on the structure of crystals,

applied to several genera of crystallized substances. Paris: Chez

Gogué & Née de la Rochelle, 1784. Image: From Crystallography

- Defining the Shape of Our Modern World. A Book Exhibit at the University

of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Commemorating the 100th Anniversary

of the Discovery of X-ray Diffraction. http://www.scs.illinois.edu/~mainzv/xray_exhibit/

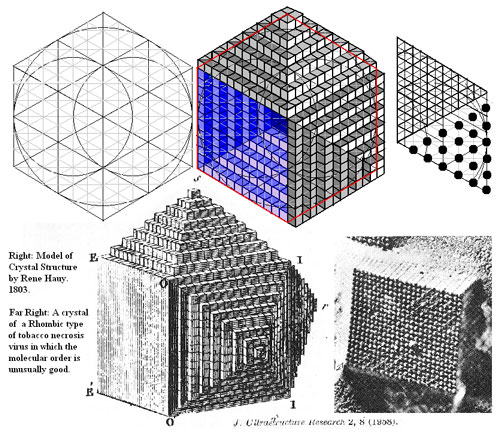

Figure 23 (right). Novum Veritas

Universalis: Top row: Haüy crystal models from 1803. Bottom row:

Tobacco mosaic virus models from 1958. http://novumveritasuniversalis.wordpress.com/2012/07/14/crystallography-part-one-orthographic-and-fischer-projections/crystal-model/.

Accessed 14 January 2013. Haüy came the Muséum in 1792 after a brief stay in prison for his refusing to take an oath to the new regime following the fall of Robespierre. Candolle arrived to study initially at the Muséum for a brief period in 1795 at the invitation of the well-known geologist Déodat de Dolomieu, and he recalls warmly and enthusiastically attending Haüy's lectures in mineralogy. After a few years back in Geneva Candolle returned in 1798 and for the next eight years (the ones before the issue of the Flore), he and Haüy were institutional colleagues: Haüy as keeper and chair of the Department of Mineralogy and Candolle as deputy to Cuvier and Lamarck. When Candolle, a Protestant, was proposed to be admitted to the botanical section of the Muséum, Haüy, a Catholic, might have been expected to vote against him, "but he voted in favor indicating that he was glad to be able to show that he did not mix religious opinions and scientific judgments [account from Gray]." Candolle's son, in editing his father's Mémoires, wrote: "The more specific idea of my father, that of the regularity [unity] of the typical plan in plants, an idea that has always driven Goethe, corresponds to the theories of Haüy on crystallization, and the law of proportions determined for the composition of a chemical body by Berzelius." Even though personally the two were not close, Candolle knew Haüy's work well and lauded it. After piecing these relations and opportunities together my expectations were high that Haüy might be the source of Candolle's diatomes. So I scoured all volumes of Haüy's Treatise and many of its precursors for the use of any variant of diatome, but I scoured in vain. It's just not there. Perhaps Haüy used it verbally in conversations with Candolle, perhaps it rests recorded in some of Haüy's lecture notes, some which still exist and are being published and analyzed, perhaps …, perhaps ..., but at present there is simply no evidence in Haüy to support Candolle's having gotten the word diatome from him. But given the absence of the word, casting Haüy as irrelevant would be rash. He did use the word clivage (cleavage), but very rarely in his works. In commenting on a work (Géographie-physique) by the Swedish mineralogist Torbern Bergman in 1795 Haüy wrote:

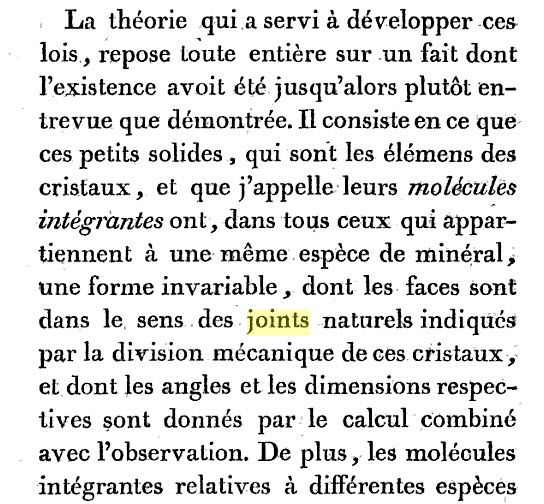

Haüy uses the word clivage/cliver only once in his Treatise (vol. 3). But to focus too closely on the word diatome itself, on the sequence of letters forming a token, is maybe to miss the idea the word conveys and that the idea might travel independently of that word -- in this case, the idea of the division of a mineral along planes of inherent joints. Very early in the first volume (1801) of the Treatise he wrote (Figure 24):

That idea of "(mechanical) division along natural joints" is underfoot continually in Haüy's Treatise; he essentially uses this phrase or its components (" .... joints naturels") capturing the idea about 175 times through the entire work. It is a cornerstone of his ideas about crystal structures and how to elucidate their basic units. One cannot read the Treatise and fail to be steeped in this idea. Candolle not only read the Treatise, but he praised it in his works. Furthermore, the mineral-like aspects of diatoms were not lost on the naturalists of the period, Candolle included: diatoms were prismatic, transparent to light, and crystalline (Roth 1797), transparent (Candolle 1805), confusable with salt crystals (molécules salines, Villars 1807), had crystalline form and structure (Agardh 1817), were crystal-shaped (crystalliformia, Lyngbye 1819), and formed a crystalline crust (croûtes cristallines, Bonnemaison 1822) on plants. Would it be surprising that upon seeing a zig-zag diatom filament and its refractive properties for the first time that Candolle had an idea, not a specific word, in his mind that fit what he saw -- the pervasive and conspicuous "division along natural joints" of Haüy? And that then he found a name to fit that idea? |

|

|

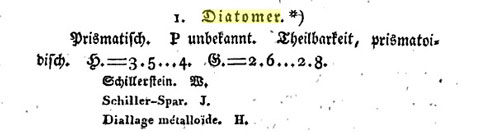

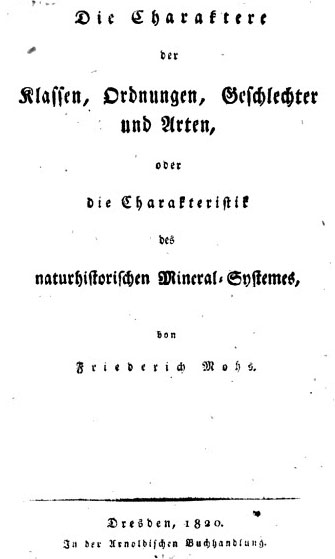

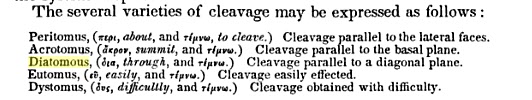

Let us clean up our observations on the mineralogical word diatomous. If one back-tracks on its use gradually from Dana and Emmons in the 1830s, one comes to rest in an 1820 text in German for students of mineralogy written by the German mineralogist Friederich Mohs, in which he uses diatomer twice, each time to describe the cleavage plane in a mineral: Schiller-Spar and Kuphon-Spar. He provides its etymology and meaning (Figure 27): From δια [dia], through, and τεμνειν, I cut (Easily cleavable in one direction) [= nacht einer Richtung leicht theilbar]. In the same year he issued an English language version of the text, published in Edinburgh, and offered diatomer [German] as diatomous [English].

Figure.

25 (above, top) Friederich Mohs (1773-1839) and

Figure 26 (above, bottom) Robert Jameson (1774-1854).

Images: Public domain.

|

| <-- 6- Diatoms - siliceous, two-shelled cells |

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

By

the 1830's the English word diatomous had become a well-established

adjective among mineralogists referring to a crystal's cleavage, its

tendency to split along inherent planes of structual weakness, planes

termed at the time as "natural joints." Yale's James Dwight

Dana in 1837 included diatomous as part of his introduction

to crystal structure (Figure 18):

By

the 1830's the English word diatomous had become a well-established

adjective among mineralogists referring to a crystal's cleavage, its

tendency to split along inherent planes of structual weakness, planes

termed at the time as "natural joints." Yale's James Dwight

Dana in 1837 included diatomous as part of his introduction

to crystal structure (Figure 18):

In

the decades surrounding 1800 mineralogy and crystallography were undergoing

fundamental changes in their theoretical understanding of the structure

of crystals and consequently in the description and classification

of them. The seed at the core of these changes and its implications

were captured by one of England's leading scientists, and it focussed

on cleavage:

In

the decades surrounding 1800 mineralogy and crystallography were undergoing

fundamental changes in their theoretical understanding of the structure

of crystals and consequently in the description and classification

of them. The seed at the core of these changes and its implications

were captured by one of England's leading scientists, and it focussed

on cleavage: Haüy

developed his ideas about crystal structure in the 1770-1780s, while

a professor at College de Cardinal Lemoine in Paris, presented them

initially in a paper in 1784 (Figure 22), had further developed them

while at the École normale and École des Mines, where

he serially published them initially in the Journal des Mines

and finally in the widely circulated 5-volume Traité de Minéralogie

(1801-1805), notably the same period during which Candolle worked

on the Flore. Haüy had observed that a crystal when broken

preferentially splits or cleaves along certain internal planes. He attempted

to explain an apparent pattern of specific cleavage planes being characteristic

of a particular kind of mineral by a model which proposed that these

planes reflected the shape of the fundamental atomistic building block

of the crystal, its so-called unit cell. Different crystals are composed

of different basic blocks, and thus by the examination of their cleavage

planes and the detailed measurement of the angles of intersection of

these planes in large crystals. one could deduce, with mathematical

rigor, the shape or form, the microgeometry, of this basic unit -- a

unit analogous in concept to that of an element that was then emerging

in chemistry and would served as the basis for the development of the

periodic table. These ideas underlay the development of the science

of crystallography, which 150 years later would lead Frankin, Watson,

Crick and Wilkins to unveil the structure of DNA.

Haüy

developed his ideas about crystal structure in the 1770-1780s, while

a professor at College de Cardinal Lemoine in Paris, presented them

initially in a paper in 1784 (Figure 22), had further developed them

while at the École normale and École des Mines, where

he serially published them initially in the Journal des Mines

and finally in the widely circulated 5-volume Traité de Minéralogie

(1801-1805), notably the same period during which Candolle worked

on the Flore. Haüy had observed that a crystal when broken

preferentially splits or cleaves along certain internal planes. He attempted

to explain an apparent pattern of specific cleavage planes being characteristic

of a particular kind of mineral by a model which proposed that these

planes reflected the shape of the fundamental atomistic building block

of the crystal, its so-called unit cell. Different crystals are composed

of different basic blocks, and thus by the examination of their cleavage

planes and the detailed measurement of the angles of intersection of

these planes in large crystals. one could deduce, with mathematical

rigor, the shape or form, the microgeometry, of this basic unit -- a

unit analogous in concept to that of an element that was then emerging

in chemistry and would served as the basis for the development of the

periodic table. These ideas underlay the development of the science

of crystallography, which 150 years later would lead Frankin, Watson,

Crick and Wilkins to unveil the structure of DNA.  .

.

Figure

24 (left). From Haüy, Treatise de Minéralogy,

vol. 1 (1801). Partial translation of text on the left:

Figure

24 (left). From Haüy, Treatise de Minéralogy,

vol. 1 (1801). Partial translation of text on the left:

The

following year the Scottish (Edinburgher) geologist Robert Jameson,

published a Manual of Mineralogy and also used diatomous,

exactly in accord with that of Mohs (Figure 27). This is not surprising

as Mohs and Jameson were students together in Freiburg under Abraham

Werner around 1800, engaged in extended geological excursions together

during the first two decades of the century, and were scientific and

intellectual confidants, especially after 1817 when Mohs was preparing

his works. "Diatomous/diatomer" may well have grown out of

discussions between the two, but it precipitated in print first in Mohs'

1820 German edition of The Characters of the Classes, Orders, Genera,

and Species, or the Characteristics of the Natural History System of

Mineralogy. It's use by Mohs is a bit different than that by Candolle,

as an adjective, not as a noun, not to describe any cleavage along natural

joints, but just a subset of them, those in which the cleavage has one

specific orientation. This is the source of the word diatomous

in mineralogy -- 15 years after the Flore.

The

following year the Scottish (Edinburgher) geologist Robert Jameson,

published a Manual of Mineralogy and also used diatomous,

exactly in accord with that of Mohs (Figure 27). This is not surprising

as Mohs and Jameson were students together in Freiburg under Abraham

Werner around 1800, engaged in extended geological excursions together

during the first two decades of the century, and were scientific and

intellectual confidants, especially after 1817 when Mohs was preparing

his works. "Diatomous/diatomer" may well have grown out of

discussions between the two, but it precipitated in print first in Mohs'

1820 German edition of The Characters of the Classes, Orders, Genera,

and Species, or the Characteristics of the Natural History System of

Mineralogy. It's use by Mohs is a bit different than that by Candolle,

as an adjective, not as a noun, not to describe any cleavage along natural

joints, but just a subset of them, those in which the cleavage has one

specific orientation. This is the source of the word diatomous

in mineralogy -- 15 years after the Flore.